Simchat Torah

The Jewish people are often referred to as the “People of the Book,” a title that reflects their deep connection to the Hebrew Bible, which includes the Five Books of Moses, the Prophets, the Psalms, and other poetic writings. These sacred texts have profoundly shaped the Judeo-Christian worldview and the foundations of many societies. The laws within these scriptures have influenced legal systems in the United States and other cultures. As promised to Abraham in Genesis 22:18, “through your offspring all nations on earth will be blessed,” the Jewish Bible has been a blessing to the world, offering some of the earliest recorded stories with clear moral messages, distinguishing between good and evil, light and darkness. The Jewish people have taken their role as stewards of these texts seriously.

Simchat Torah, celebrated on the eighth day of the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot), is a joyous occasion when Jews worldwide celebrate God’s gift of the Torah. In synagogues and on the streets of cities like Tel Aviv, Torah scrolls are raised high, and people dance and rejoice. You can watch a vibrant celebration of Simchat Torah in Tel Aviv here: YouTube link.

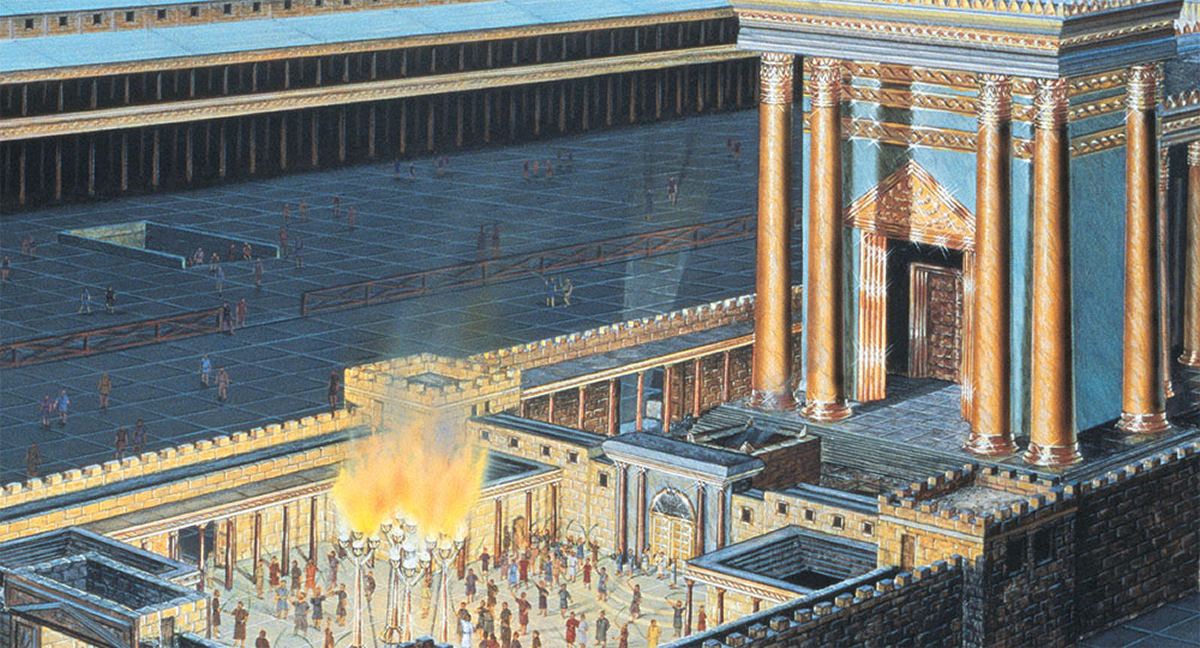

This tradition likely traces back to the time of Ezra, as described in Nehemiah 8. The passage recounts how, on the first day of the seventh month (Rosh Hashanah), the Jewish people gathered in Jerusalem’s square before the Water Gate, where priests brought water from the Pool of Siloam each morning during the Feast of Tabernacles. At this time, the people were rebuilding Jerusalem’s walls and sought to restore their spiritual lives by listening to Ezra read from the Torah.

Nehemiah 8:1-3, 9-10, 14-18 (paraphrased):

All the people gathered as one in the square before the Water Gate and asked Ezra, the teacher of the Law, to bring out the Book of the Law of Moses, which God had commanded for Israel. On the first day of the seventh month, Ezra read the Law aloud from daybreak until noon to an assembly of men, women, and all who could understand. The people listened attentively.

Ezra and Nehemiah said, “This day is holy to the Lord your God. Do not mourn or weep,” for the people had been weeping as they heard the Law, realizing they had not followed it. Nehemiah added, “Go, enjoy choice food and sweet drinks, and share with those who have nothing. Do not grieve, for the joy of the Lord is your strength.”

The people discovered in the Law that during the festival of the seventh month, they were to live in temporary shelters. They were instructed to gather branches from olive, wild olive, myrtle, palm, and shade trees to build these shelters. So, they built shelters on their roofs, in courtyards, in the courts of the house of God, and in the squares by the Water Gate and the Gate of Ephraim. The entire community that had returned from exile celebrated Sukkot in this way, a celebration not seen since the days of Joshua son of Nun. Their joy was immense.

For seven days, Ezra read from the Book of the Law, and on the eighth day, as prescribed, they held an assembly. This eighth day has become known as Simchat Torah, a day to rejoice in the Torah as the source of life and guidance.

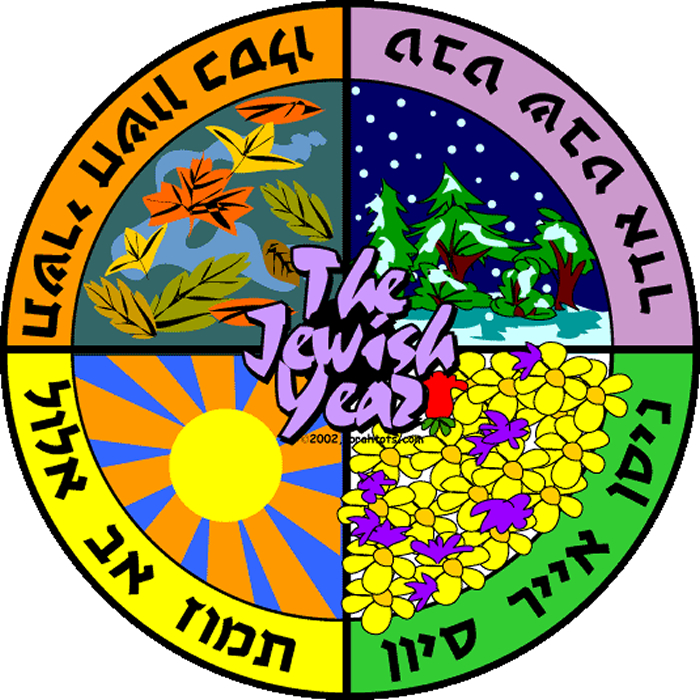

This passage from Nehemiah highlights the public reading of scripture, ensuring all could hear God’s words. This practice led to the establishment of a weekly system for reading Torah portions, called parashot, in synagogues. There are 54 parashot (sections of the Torah), and the full cycle is read over the course of one Jewish year. On Simchat Torah, the final portion of Deuteronomy is read, followed immediately by the opening of Genesis, symbolizing the continuous, unbroken cycle of Torah study.

© 2025 B Arnold Stein